SAFEVISITOR BLOG

Wait -- is Code Yellow a shooter or a bus problem?

“Attention, Code Yellow.” The voice crackles over the intercom, stopping everyone in their tracks. Can’t quite remember -- isn’t Code Yellow a problem in the bus drop-off area? Or is that when we summon the imaginary “Ms. Smithers” to the office? Or isn’t that a Signal Three?

Anyone who’s watched a spy movie or one of those films showing the behind-the-scenes operations in the Pentagon has heard all sorts of interesting code words. “The President has ordered everyone to Defcon-Two, so we need to implement Code Green.” It’s pretty cool to know all those secret codes are in use, making sure people who shouldn’t have access to information won’t know what’s happening.

Schools and other facilities often adopt similar secret codes. The justification is usually that only the people who are required to take action (such as teachers or department managers) will know what’s happening, so other occupants of the facility (such as students or employees) won’t panic.

The intent may seem reasonable, but there’s an inherent problem with codes: people forget them. When they hear the code words, they may not remember what they’re supposed to mean. And if they’re the person in a crisis situation, they might not have the presence of mind to call for a Code Yellow, a Code Red, or a Code Fuchsia. Instead, they’ll panic or freeze.

We live in a different world than we did 10 or 20 years ago. Media coverage of mass shootings, school violence, and terrorist acts have sharpened awareness. That’s true even among young students. Even if they haven’t seen the news stories, they’ve heard their parents and classmates discuss shootings and other acts. Today’s students are every bit as uneasy about the potential for an incident as their grandparents were when they were practicing duck-and-cover drills.

Preparing to deal with dangerous incidents is serious business. Playing around with code words and similar strategies can compound the danger by creating confusion. It’s far better to use plain English and state exactly what you want people to do. If your school needs to be locked down because of a potential threat, saying “Lockdown now” over the intercom will stir people into action far more effectively than asking “Ms. Smithers” to visit the office.

There’s a part of our brains that’s sometimes derided as “reptilian.” It’s the area of the brain that makes instinctive responses to situations. If we see an object flying toward our heads, we duck. If our feet slip, we automatically reach out for something that will allow us to steady ourselves. As intelligent, rational animals, we’re a bit ashamed of our reptilian reactions, but they’re what keep us alive. When we see a shooter entering a building, we don’t have the luxury of carefully analyzing the situation and considering alternatives. We need to get to safety immediately.

“Code Yellow” doesn’t kick the reptilian brain into action, but “Shooter! Take cover!” will. If we want people to evacuate a burning building, we yell “Fire! Get out!” for a reason. Everyone knows what that means and what they’re supposed to do.

In addition to using plain English, it’s important to make sure that everyone who can call an alert uses the same words. If one administrator says “Lockdown now!” and another says something about taking cover, they may not get the same response. That’s why many schools use common language such as the Standard Response Protocol [http://iloveuguys.org/srp.html] to notify occupants about emergencies. They also regularly practice the actions occupants are supposed to take when they hear those words. For example, lockdowns are triggered by the phrase “Lockdown! Locks, Lights, Out of Sight.” Even the youngest students can easily memorize that phrase, so they know exactly what to do to protect themselves.

If you’re responsible for occupants in multiple buildings, such as a school district with multiple schools, it’s a good idea to use the same protocol in every building. That way, if staff members are working in a different building, or if students move from an elementary to a middle school, they’ll automatically know how to react.

Standard protocols may not be as much fun as code words, but in a real-life emergency, they make a tremendous difference in protecting everyone’s safety.

Is your security toolkit complete?

One of the things that separates law enforcement professionals from average civilians is how the two groups approach a situation. When the average person walks into a building, his or her attention tends to be focused solely on the destination or the purpose for the visit. But when a police officer enters the same building, he or she instinctively scans in every direction, looking for any potential threat sources, mapping out escape routes, and evaluating what’s happening.

Similarly, when businesses or organizations talk about security, they tend to talk about specific things. Maybe we need cameras. Or a badge system. Or a stronger door. But when those of us who have worked in law enforcement talk about security, we take a more holistic approach. That’s because true security encompasses many different elements that work together in a synergistic fashion. Any one of those elements offers some protection; multiple elements work together in ways that provide a much higher level of safety.

When I’m asked about how a school, a company, or another organization should approach facility safety, I suggest they develop what I call a security toolkit. Just as your toolkit at home includes a variety of devices to help you perform an even wider variety of tasks, your security toolkit should include multiple items that address many different aspects of security. What are the tools that belong in your kit?

Start with a Security Assessment. Invite a professional consultant or local law enforcement to walk through your facility, identify potential vulnerabilities, and make recommendations.

Create a Policy. A security policy explain the reasons behind security, everyone’s responsibility, and the steps to take when something goes wrong, such as who is authorized to dial 911. When people aren’t sure how to approach a situation, that policy provides guidance.

Threat Assessment Team. Create a group from your organization (and possibly pair them with representatives from local law enforcement). Give them the responsibility to think about and identify the threats your organization might face and steps that could be taken to address them.

Background Checks. You won’t be surprised that the head of a background check provider advocates background checks, but it’s one of the most effective ways to prevent problems. A resume tells you how someone wants you to think about them, but a background check can share what they don’t want you to know.

Visitor Management. If someone doesn’t belong in your facility, you shouldn’t let them in. If you do allow them to visit, you should know where they are and what they’re doing. Formal systems like SafeVisitor help, but you can also use policies such as ensuring that visitors are always escorted through your facility.

Anonymous Reporting. After most workplace shootings, we hear that someone knew that something wasn’t right, but they were afraid to say anything. So provide ways that employees can call attention to strange behavior or situations without having to identify themselves. An employee who jokes about bringing a gun to work probably isn’t kidding around.

Integrated Communication. Have the equipment and processes in place so decision-makers and first responders can communicate clearly in an emergency situation.

Training. The training your team needs depends on your situations and activities. For example, if your team members travel frequently, make sure they know how to protect themselves on the road. Also provide training about domestic violence awareness, so employees can recognize when there’s a problem and so the entire team knows how to protect victims.

Hardware/Construction/Renovations. This is the physical part of your toolkit, eliminating and minimizing vulnerabilities by using technology and physical alternations to your facility. No single approach is right for every organization. Make your choices based upon the vulnerabilities your assessment identifies.

Finally, your security toolkit should also address what you’ll do if your security is breached. We’ll hope that your security toolkit prevents that from happening, but it’s wise to have a plan just in case.

Contact us for more information on creating a security toolkit.

Active Shooter: Facility Security Starts Far From Your Front Door

It never ceases to amaze me how many organizations establish “security” for their buildings by stationing a sleepy security guard or a doorman with a clipboard at the entrance. If someone who was planning mayhem … such as a shooter … shoved past the front desk, about the only defense that guard can offer is to yell, “Hey! You can’t go in there!” Then he might call his boss to see what he should do about it.

Even worse, those glorified hall monitors rarely pay attention to what’s signed on those clipboards. I could write “Charles Manson” for my name, and nobody would blink. Nor do most verify my credentials or check to see if I belong there. If I were a domestic abuser who wanted to get to my estranged spouse, all I’d have to do is claim I had a meeting with one of her co-workers (whose names I would know from conversations). I might have to wear a visitor’s badge, but that’s about it.

I’m not trying to be an alarmist, but we live in an era in which workplace and school shootings happen often enough that most earn just a quick spot on the news feed.

Take April’s shooting at YouTube’s headquarters in the heart of Silicon Valley. Nasim Majafi Aghdam simply walked into a courtyard in the company’s complex and opened fire on people she apparently didn’t know, wounding three before turning the gun on herself. She evidently had grievances with the company’s business practices, and these three just happened to be in the wrong place when she walked onto the property looking for someone to punish.

What’s to stop someone who’s unbalanced and has a gripe with your company or one of your employees from doing the same?

If you truly want to protect your students, your employees, your customers, or anyone occupying your facilities, you need to recognize that your front door is your point of last resort. It’s your last opportunity to control access to the facility. You may not be able to stop someone with criminal intent, but you can slow his or entry and alert authorities. Once the individual crosses that barrier, it’s too late. Even if the police arrive within a couple minutes, it’s likely that the damage will have been done.

So you need to shift your thinking. Instead of asking, “What do we do when someone enters our building?,” you need to ask, “What can we do to keep the wrong people out of our building in the first place? How do we make it clear that our location is unwelcome?”

Most people think of those as security decisions, but they’re really policy decisions that should become a central part of your organization’s culture. “Keeping our people safe” should be one of your organization’s guiding values. Finding the best way to do that then becomes the responsibility of everyone from the very top down.

There aren’t any one-plan-fits-all building security approaches, so you need to approach your situation with the specifics that make sense for your organization and facility. It may be a visitor management system, some kind of mandatory prior authorization for visits, moving the front line of security from the front door to the entry drive, creating an open-door policy in which victims of domestic abuse can feel comfortable sharing their concerns, holding a tabletop exercise to see how you’d handle specific scenarios -- the list of potential elements is endless.

We don’t need to be paranoid, thinking that everyone is out to get us in every manner imaginable, but we do need to be practical and realistic. We need to give serious thought to potential threats and ask ourselves what we can do to head each off. We need to invite first responders into our facilities and ask what makes them nervous, because they constantly have to assess risks as part of their job. They immediately notice things you’d never think about.

Employers and building managers don’t blink when they’re asked to install sprinkler systems, extinguishers, alarms, and other elements of fire protection. They don’t hesitate to identify shelter locations to protect employees and visitors during times of severe weather. So it’s no stretch to expand that thinking into protecting everyone from someone who means to do harm. Real security starts with intelligent thinking.

School Active Shooters: Getting "Left of Bang"

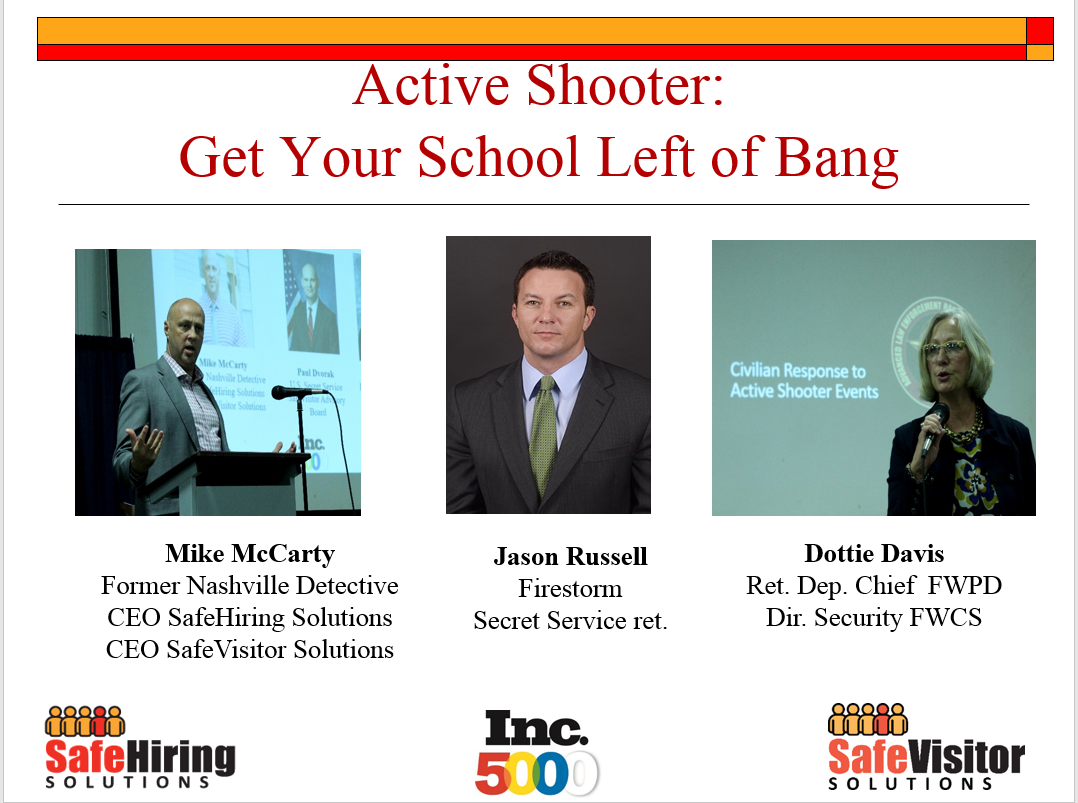

There is so much noise these days about how to make schools safer. The vast majority is counter-productive and pushing schools in the wrong direction. Watch the following active shooter webinar by experts from law enforcement, Secret Service and school security as they walk you through a process of understanding that school active shooter incidents have predictable behaviors.

Active Shooters: Stop Reacting, Start Preventing

Every time there’s a shooting at a school or a workplace, the arguments begin. We need more police officers stationed in the buildings. We need to arm teachers or encourage employees to carry handguns. We should invest in smokescreen systems or bulletproof partitions. Everyone should hide from the shooter. Everyone should run from the shooter. Everyone should confront the shooter.

We’re having the wrong argument. Once someone who intends to do harm is inside your school or your business, all you can do is react. And at that point, it’s too late. Whether you run, hide, fight, or something else, your school or business is going to be the site of violence and possibly death, permanently transforming the lives of everyone involved.

Instead of focusing on reacting to a shooter or other intruder’s presence, what we should concentrate on is keeping that shooter out of the school or workplace. If a shooter can’t get into your facility, he or she can’t cause mayhem.

We can learn from the professionals we trust to protect some of the world’s most important people: the U.S. Secret Service. The image that springs to mind is the agent who jumps in front of a would-be assassin, taking a bullet intended for the President, but the Secret Service puts far more effort into making sure people with bad intent don’t get anywhere near the individual they’re protecting. They’ll react if they have to, but far more of their time and energy goes into prevention.

In preparing, we first need to get past the myth that these shootings are random events triggered by someone’s temper or someone who just “snapped.” The FBI has studied shooting extensively, and says “these are not spontaneous, emotion-driven, impulsive crimes emanating from a person’s immediate anger or fear.” The reality is that most of events are not impulsive; they’re coldly and carefully planned.

There’s a parallel in domestic violence cases. The popular “wisdom” is that people who commit violence against family members were “pushed” into it or were “triggered” by something the victim said or did. As a former violent crimes detective, I can tell you that’s nonsense. There’s a discernable pattern that offenders follow. When law enforcement and the judicial system know that pattern and intervene in the early stages, there’s a marked reduction in homicide and other violent acts. (Another reason domestic violence is important to mention is that it’s actually been related to 54 percent of mass shootings.)

Prevention involves several components. Staff members need to be able to recognize the signs and behaviors that usually precede a violent act -- like the threats and other behaviors that have been observed before 85 percent of school shootings.

We have to create a culture in which people aren’t afraid to report suspicious behaviors. Too many people are afraid of hurting someone’s feelings or accusing someone who may be innocent. After most shootings, we hear that the shooter showed signs of being dangerous, but nobody was willing to speak up. Similarly, we have to share information. For example, school leaders need to be in regular conversations with local police. Police in one community need to talk with the county sheriff and their neighboring departments. And all parties to be trained in assessing threats through the use of lethality indicators.

Training is one of the most important components, and it can’t be a one-and-done approach. One of the best kinds is the “tabletop” simulation in which multiple parties gather to discuss a simulated scenario. For a school, the simulation might involve the building administrators, the superintendent, the head of security, and representatives from the local police and fire departments. An outside facilitator narrates a scenario, and everyone discusses their role and how they would respond. (I’d also recommend involving the head custodian, who knows the building inside and out, and who will have a practical approach to identifying flaws in the other participants’ responses.)

If you really want to protect the occupants of your buildings, don’t waste time in philosophical arguments over what they should do if an intruder is present. Instead, do everything you can to keep that intruder from getting in there in the first place.

Articles

-

Active Shooter

5

- Dec 3, 2018 Wait -- is Code Yellow a shooter or a bus problem? Dec 3, 2018

- Jul 2, 2018 Is your security toolkit complete? Jul 2, 2018

- Jun 1, 2018 Active Shooter: Facility Security Starts Far From Your Front Door Jun 1, 2018

- May 23, 2018 School Active Shooters: Getting "Left of Bang" May 23, 2018

- May 7, 2018 Active Shooters: Stop Reacting, Start Preventing May 7, 2018

-

Background Checks

4

- Oct 25, 2017 How Do We Comply With Indiana HEA 1079? Oct 25, 2017

- Oct 3, 2017 Top 5 Problems with Vendor Background Checks Oct 3, 2017

- Aug 25, 2017 Can I manage employee background checks in a visitor management system? Aug 25, 2017

- Aug 17, 2017 Do Visitor Management Systems Integrate with Comprehensive Background Checks? Aug 17, 2017

-

Building Security

3

- Jun 3, 2019 Preventing “road rage” in your parking lot Jun 3, 2019

- Sep 4, 2018 Metal Detectors Aren't a Magical Safety Solution Sep 4, 2018

- Feb 27, 2018 Making Sure Your Building is Safe No Matter Who is There Feb 27, 2018

-

Cloud Hosting

1

- Nov 7, 2017 Visitor Management System: Cloud Hosting vs Local Server Nov 7, 2017

-

Concealed Carry

1

- Feb 1, 2019 How should you deal with concealed carry? Feb 1, 2019

-

Corporate Security

2

- Aug 1, 2018 How a Warrior Views Your Facility Aug 1, 2018

- Dec 7, 2017 How to Protect Yourself at Work Dec 7, 2017

-

Emergency Alerts

2

- Nov 1, 2018 When an Excluded Visitor Creates a Disruption Nov 1, 2018

- Jan 9, 2018 How Our Emergency Button Helps Put the 'Safe' in SafeVisitor How Our Emergency Button Helps Put the 'Safe' in SafeVisitor Jan 9, 2018

-

Excluded Parties

1

- Sep 11, 2017 How to Create Visitor Management Excluded Parties Lists Sep 11, 2017

-

Facial Recognition

1

- Aug 26, 2019 Use and Misuse of Facial Recognition Software Aug 26, 2019

-

Geofence

2

- Oct 6, 2017 How Does Geo-Fence Expand Your Security Perimeter? Oct 6, 2017

- Aug 22, 2017 Visitor Management: How Can A Geofence Protect My Organization? Aug 22, 2017

-

Pricing

1

- Sep 13, 2017 What is the Cost of a Visitor Management System? Sep 13, 2017

-

Reunification

2

- Mar 9, 2021 Visitor Management System for Schools Mar 9, 2021

- May 1, 2019 Developing a plan for reunification after emergencies May 1, 2019

-

School Visitor Management

13

- Mar 9, 2021 Visitor Management System for Schools Mar 9, 2021

- Oct 18, 2019 How to Make Schools Safer With A School Visitor Check-In System Oct 18, 2019

- Oct 4, 2019 What is Best Visitor Management System for Schools? Oct 4, 2019

- Sep 24, 2019 School Visitor Management Systems Are The Foundation for Security Sep 24, 2019

- Aug 30, 2019 What Should a Visitor Management System for Schools Do? Aug 30, 2019

- Aug 8, 2019 Visitor Management System for Schools Aug 8, 2019

- Apr 1, 2019 Anonymous reporting systems enhance safety Apr 1, 2019

- Mar 1, 2019 Someone phoned in a bomb threat. Now what? Mar 1, 2019

- Jan 2, 2019 Are Your After-School Events Safe Places? Jan 2, 2019

- Nov 14, 2017 What’s the Purpose of a Visitor Management System? Nov 14, 2017

- Sep 22, 2017 Are You Keeping Students Safe with a Quality Visitor Management System? Sep 22, 2017

- Sep 11, 2017 How to Create Visitor Management Excluded Parties Lists Sep 11, 2017

- Aug 29, 2017 What Is the Best School Visitor Management System? Aug 29, 2017

-

Sex Offender Search

2

- Nov 1, 2017 Is the Visitor Management System Sex Offender Data Up To Date? Nov 1, 2017

- Aug 31, 2017 Visitor Management System: Do You Really Know All of Your Visitors? Aug 31, 2017

-

Vendor Management

1

- Oct 1, 2018 Visitor Management: How Well Do You Trust Vendors in Your Facilities? Oct 1, 2018

-

Visitor Management

2

- Sep 15, 2019 Visitor Management Software: Security Technology Removes Stress Sep 15, 2019

- Sep 9, 2019 What is Visitor Management System? Sep 9, 2019

-

Volunteer Management

2

- Nov 21, 2017 How do I Conduct a Kiwanis Background Check? Nov 21, 2017

- Sep 25, 2017 Creating a Volunteer Background Screening Consortium Sep 25, 2017

-

WA WATCH Background Check

1

- Jan 15, 2018 WA State Police WATCH Volunteer Background Checks Jan 15, 2018

-

visitor kiosk

1

- Aug 15, 2019 Visitor Management Kiosk Aug 15, 2019